In the G Burns Jug Band, I perform a mix of blues, hillbilly, and early jazz music from the 1920s and 1930s. It’s a collection that some would refer to as “pre-war music” (referring to World War II). This is a particularly special era for lovers of folk and traditional music because it was a time in which record companies first began scouting for talented musicians in rural and lower-class parts of the country. Before this, recording companies relied on the talents of trained urban musicians in cities like New York, and they catered to the tastes of the upper classes: classical music or tin pan alley songs written out by professional composers. When recording technology advanced enough to be portable, scouts began venturing into Southern cities and remote rural regions. They recorded local musicians playing in styles unique to their own regions, and as a result, a lot of “unusual” music was recorded. Instead of operatic singers performing the works of Puccini, or slick crooners singing cute numbers about falling in love, companies were recording mountain musicians that had built their own banjos from kitchen pots and the hides of family pets, and used them to sing centuries-old ballads about murdering your lover. They also recorded, to provide another example, jug bands.

I’m guessing a good many of the folks reading this have never heard a jug band, or even heard of a jug band. In the broadest sense, a jug band can be any band which uses a ceramic jug as a bass instrument. Technically, the jug is a wind instrument because the player buzzes their lips and blows into the jug, using it as a resonator. By adjusting their embouchure, or the tenseness of their lips, the player creates a musical tone resembling an upright bass being bowed with a weedwacker. In the pre-war era, the instrument was most popular in Southern African American string bands, where it was combined with guitars, mandolins, banjos, and fiddles, and even clarinets, saxophones, cornets, and tubas.

In September of this year, the G Burns Jug Band was invited to Louisville, Kentucky to perform at the National Jug Band Jubilee (yes, it’s a thing). It was a special invitation because of Louisville’s historic importance to jug band history, which I’ll describe later, but also because I am a 5th generation Kentuckian. All of my family is there, and Louisville played an important role in shaping my early musical life. The band decided to book a few dates before the Jubilee and visit a few other towns. What follows is a town-by-town report that I wrote for our band newsletter, detailing the trip.

JOURNEY TO THE MOTHERLAND

We have returned from our journey through the South, and it was revelatory. On a personal level, and in terms of the band’s career, the trip felt transformative, refreshing, and emboldening. It’s not something I could measure or describe so much in terms of fees commanded or CDs sold. It was something I sensed in the the people around us, and in the experience of moving through the landscapes that created the music that we play: swamps, piney forests, rolling hills, the endless panoramas of lush green (we’re based in the southern California desert, mind you). But also those storied man-made places, the legendary rows of dive bar venues, the meandering country roads tracing the contours of creeks to the top of a ridge, the bridges and barges whose routes have moved people and music around the country for generations. Everywhere we went, there was some vivid quality of connectedness. The music we play was connected to those landscapes and those places, it was connected to the weather, it was connected to the food, it was connected to the language and the accents. The music connected families, it connected friends. That’s what the transformation was about: connection.

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA

Flying over the bayou country of Louisiana. There's probably more water in this picture than in all of Southern California

Meghann Welsh - our tenor banjo-ist, vocalist, and Kalabash teacher - and I began our journey by leaving the driest place in the country and flying straight to the wettest: New Orleans. Originally I had hoped to bring the band here, but alas, budgets and schedules couldn't handle it, so the two of us went for a 48-hour vacation

New Orleans is of course one of the great cities of American music and American music history. In the early 20th century, it was a crucible of African-American musical innovation and, equally important, it was a river town. At the end of the Mississippi River, New Orleans music and musicians had access to relatively rapid travel throughout the country. Most of the historic jug bands that recorded were formed near the shores of the Mississippi River or the Ohio River which feeds into it: The Memphis Jug Band, Clifford’s Louisville Jug Band, The Cincinnati Jug Band. The influence of New Orleans jazz and ragtime music in many of them, particularly the Louisville bands, and the role of the rivers is undeniable.

The Natchez on the Mississippi River in New Orleans

Meghann and I solicited advice about venues and bands from our well-traveled friends, who steered us in the right direction. The city is so densely packed with quality music that, over and over again, we found ourselves stumbling upon their highly-recommended spots without even trying. Our favorite - and the favorite of most of our friends - was The Spotted Cat, where we snapped this short video.

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA

After all the etouffee and sazeracs, we drove to Birmingham and picked up Jonathan, Batya, and Tim for our first concert - a house concert at the home of the Stouts. Regular attendees of our monthly Barn Dance shows at the Black Cat Bar might remember Rebecca Stout, the amazing flatfoot dancer who performed at our April 2016 show. Rebecca calls Los Angeles home now but grew up in Birmingham, and has devoted her life to studying and sharing the folk culture of the South and supporting others who do the same. When we asked her for advice about places to play in Birmingham, she quickly enlisted the help of her siblings there to set up a house concert.

Rebecca was even able to join us in Birmingham for the show, which then became something of a minor family reunion, and danced with us once more. After her family put us up for the evening, we were treated to a favorite Stout family breakfast of grits (no sugar, thank you very much!), eggs, and bacon, complete with chicory coffee from New Orleans. In case you ever doubted: southern hospitality is real, y'all.

FRANKLIN, TENNESSEE

Our Tennessee show was at Kimbro's Legendary Pickin' Parlor in the town of Franklin, just far enough outside of Nashville to avoid the calamity of Music Row while still drawing on its immense reserve of talent. I mean, there's a sign out front, sadly dated now, that says "Haggard Plays Here". Inside, the walls were papered with old Kimbro's showbills from modern troubadours like Pokey LaFarge who still come to play in a place that feels refreshingly casual - neither a dive bar nor a craft gastropub.

Live at Kimbro's Legendary Pickin Parlor. Thanks for the photo, Ashley!

The show was lightly attended, as shows sometimes are, yet it brought out just the right people. We were delighted to be reunited with San Diegan friends who had moved to Nashville last year, and make new friends in the group Route 40, a progressive Bluegrass trio that was as indebted to Yes or King Crimson as it was Bill Monroe and the Stanley Brothers. We even managed to sneak ourselves into an article of The Tennessean newspaper, ensuring we will live on forever in the Volunteer State. Our stay was all too short, and the next morning we left for the Bluegrass state.

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY

Louisville is a special place to me. It has always been a town I knew and explored primarily through music. I grew up an hour outside of it and went there often. My dad is a musician and brought me to to the city see his favorite performers and songwriters whenever venues allowed. Included in these trips was an annual visit to the Kentucky State Fair in Louisville. We'd tour the horses and livestock, talk to Freddy Farm Bureau, eat fried food, and Dad would take us to see the Juggernaut Jug Band, a folk revival group that formed in the 70s and played the fair every year. It was always a fun memory of being a kid but also my introduction to the idea of "jug band music" and its connection to the place in which we lived.

Stu Helm of the Juggernaut Jug Band, and co-founder of the National Jug Band Jubilee

Jug bands and folk music generally didn't become a big part of my life for years to come, but Louisville remained my source for music. By the time I was in high school and old enough to drive, I was going there at least once a week. I searched for records at Ear-X-Tacy. I bought my first acoustic guitar at Guitar Emporium (we used it on our tour). I went to all-ages shows at the Keswick Democratic Club and had my first experiences of being part of a music scene: of having bands that I saw often, whose merch I bought religiously, and with whom I occasionally shared a word.

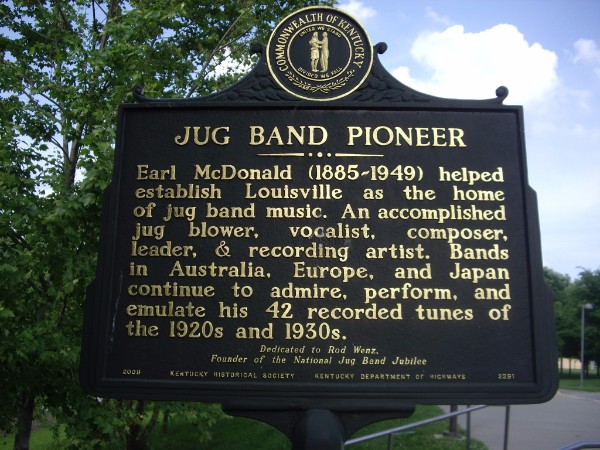

Aside from my personal experience, Louisville is a special place for the music we play because it was home to the first bands with jug-blowers to record. In the 1920s, black bandleaders like Earl McDonald and Clifford Hayes used jugs in bands inspired by the jazz music they heard coming out of New Orleans, and vaudeville blues vocalist Sarah Martin used the jug in her recordings. Their work would inspire bands in other cities across the South to expand the idea of "jug band music" to incorporate virtually all of black musical culture in America at the time. Depending on the band or even the tune, the recordings of jug bands can span jazz, ragtime, vaudeville, blues, and even gospel.

Earl McDonald's Dixieland Jug Blowers c.1926

In other words, "jug band music" as a style is hard to pin down or define. It seems to exist in between prevailing categories of American music that are more familiar to most. It's sometimes too jazzy to be blues, sometimes too bluesy to be jazz. For blues-lovers, even the bluesy jug bands seem to fall between the cracks. When it comes to iconic blues imagery, we either imagine the southern country bluesman playing acoustic guitar solo on the porch, or we imagine the electrified bands of northern cities like Chicago. By comparison, there’s very little love given to the blues mandolin players or blues fiddlers of jug bands from southern cities. All of this in-betweenness is even mirrored in the geography of the old jug bands, and their connection to the Mississippi River, which sits in between the South and the American West, and the Ohio River, which sits in between the South and the North.

This history, and more specifically the neglect of this history in the grand narratives of American music, was the impetus for the formation of the National Jug Band Jubilee. Members of the Juggernaut Jug Band, their families, and roots music lovers of Louisville launched the festival in 2005 to bring renewed attention and appreciation to this music through live performance, educational outreach, and historical preservation.

Historical marker commemorating jug band leader Earl McDonald, dedicated to the founder of the Jubilee and placed directly behind the Jubilee stage at the Brown-Forman Amphitheater.

It was a great honor to be invited to the Jubilee, and though I looked forward to it a great deal, I had not anticipated the feeling I experienced as my own personal nostalgia began to overlap with this history which had always felt a little more distant or abstract, as fascinating, wonderful, and fun as it was. Our stay in Louisville began with an afternoon assembly performance at Lincoln Performing Arts School, a cutting-edge publicly funded elementary school with an arts-centric charter. We have played many shows in which I've said my few words about the history of jug band music, but at this show, I couldn't help but remember being the age of those students and hearing that very story myself in that very city.

Sharing the story of jug band music with Louisville elementary school students

The Jubilee itself was a beautiful event at the Brown-Forman Amphitheater on the banks of the Ohio River with a great deal of my extended family in attendance. Our set fell between the wonderful Ever-Lovin Jug Band, with whom we formed a superband with Jim Kweskin last January, and the Juggernaut Jug Band themselves. After the Juggernaut's set, I found bandleader Stu Helm backstage. We shook hands and he immediately began sharing stories of seeking out and learning from the last of the city's black jug blowers in the early days of his band.

On the Big Four Bridge, a pedestrian bridge spanning the Ohio River and connecting Kentucky to Indiana.

The following morning, Meghann and I visited Louisville Cemetery, the oldest African-American cemetery in the city and final resting place of many Louisville's jug band musicians. It is smaller and more modest than other's in the city. As charming as the relatively shaggy, partly unmowed grounds were, its condition seemed to reinforce the necessity of the Jubilee. Until recently, many important black Louisville musicians, jug band or otherwise, had no marker on their burial site. The Jubilee and the Kentuckiana Blues Society have worked together in recent years to correct this by commissioning headstones commemorating the contributions of these individuals to American music.

Louisville Cemetery at the grave of Sara Martin, the vocalist whose Jug Band Blues we recorded on our second album, The Southern Pacific and The Santa Fe. Her previously unmarked grave received this marker in 2014 through joint efforts of the Jubilee and the Kentuckiana Blues Society.

From there, Meghann and I travelled an hour outside of Louisville to see my family and my hometown. While we were there, spending the last day of our amazing trip, we went to the same place I always go every time I visit home: a lookout point my great-grandfather helped build during the Great Depression for the WPA. From it, you can see all of the town and the massive Ohio River. I sat there a while and let my mind wander a little after a week of constant motion.

I watched the barges float down the river more or less as they have for over a century. I thought about all of that water working its way back to New Orleans where we had started our trip. I thought about all the roustabouts that had spread their songs through the river valleys while working on those boats. I thought about the Old Darling Distillery which produced bourbon in town in the late 19th century, and wondered if the old musicians ever got their hands on some of their product (where'd you think all those jugs came from?).

There was an all-too-brief sense of clarity and, again, connection between our music, my past, and the history of a place which will always be, in some sense, home. In the middle of my daydreaming, a lyric came to me from an old jug band song: "You may leave, but this will bring you back."